Flexibility and original craftsmanship ensure continuity

Putting oneself on the map as a start-up machining workshop is certainly no easy task in these times. It requires originality, dynamism and perhaps more than ever the ability to switch very quickly. These are all criteria that make up the DNA of DMC in Maasmechelen, led by Bart Derenette.

The young entrepreneur started the business three years ago, when he completed his studies as an engineer in electromechanics. Clearly not an obvious move. Derenette: "I come from a family of installers, specializing mainly in solar panels, heat pumps and air conditioning, but at some point I really wanted to do something else." That reorientation required a high degree of self-training in both machining techniques, as well as coding in Autodesk fusion 360, but was far from rewarding for the young engineer. In the meantime, his often idiosyncratic approach has found acceptance among a growing clientele, who are happy to fall back on DMC for their overhauls or the manufacture of spare parts.

Fast switching

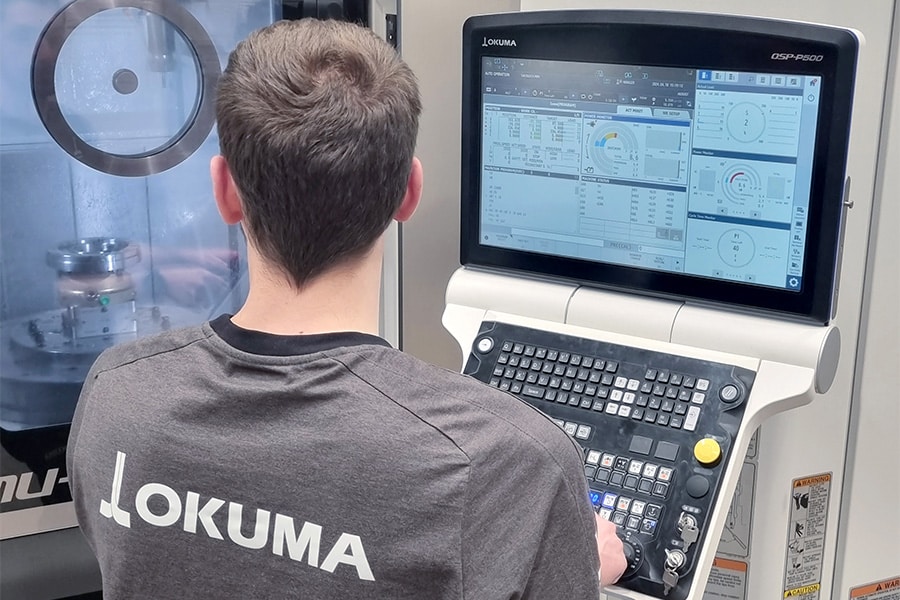

The company has therefore continued to invest steadily in recent years: the purchase of a vertical machining center and a Haas lathe, among others, was followed by a plasma cutter and a TRUMPF bending lathe. And that's ample, given the limited working area, yet Derenette puts the relative overcapacity into perspective: "This apparent opulence regularly comes down to a necessity, and allows us to move quickly and offer the most diverse solutions to a broad clientele. After all, everything you have in house you can offer." In addition to the know-how, the diversity in the machinery park is clearly the basis for DMC's flexibility and quick switching ability. "The close cooperation with my brother and father within the company also ensures continuous, operational knowledge transfer," Derenette said.

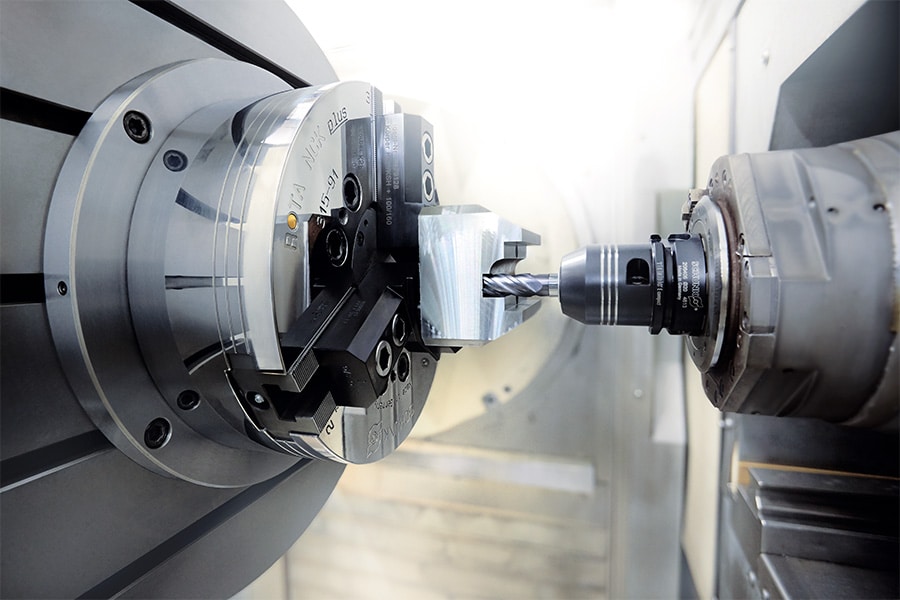

Beautiful letters of nobility

Machining is its core business until further notice, and anno 2021 DMC can present letters of adulation from a very diverse clientele. One in particular is a major player in industrial chemistry, for whom the company performs specialized turning and milling work. Derenette: "These are usually revisions of production parts, but optimizations or even reverse engineering of existing parts in stainless steel also occur regularly. In the chemical industry, this involves valves or reactor parts for which the customer usually gives you a very clear deadline. Production doesn't like to wait." Derenette also regularly co-builds special parts for the custom bike and automotive world with which his family has a strong affinity. A good example was a custom air intake that DMC was allowed to build for a rally car. Says Derenette, "Normally these kinds of parts belong on a four- or even five-axle; only we don't have that." An idiosyncratic approach clearly came in handy here. "By being creative with the alignment and fixturing options of this three-axle Haas VF2SSYT, you end up pushing the potential of the machine," Derenette states.

Short on the ball

The ability to deal quickly with technical challenges is therefore an important spearhead for the further development of the company. Here it can fall back on a number of strengths: on the one hand, there is the flexibility and ad hoc approach to technical issues whereby very short notice is taken. On the other hand, there is the diversity of supply, where rejecting an assignment is never an option. Derenette: "The only limitation can possibly be the material that is not in stock at that moment, for example. Although we have some excellent suppliers who help support our flexibility." Another strong point is that for new, unique pieces, DMC can deliver a preliminary design to the customer a priori with the 3D printer. This allows one to anticipate very many problems dimensionally and shape-wise, more than what can be classically extracted from a drawing.